[ad_1]

Mayo recognizes 60 years of transplant innovation

Charlotte Markle, 81, is among the world’s longest-surviving kidney transplant recipients. Her transplant at Mayo Clinic was over 57 years ago on March 2, 1966.

It followed Mayo Clinic’s first kidney transplant on Nov. 25, 1963, which was Mayo’s first solid organ transplant of any kind. Charlotte is Mayo’s longest-surviving transplant recipient.

She attributes her place in medical history to her loved ones and her care team.

“I thank my husband and my family and the doctors that I had,” says Charlotte, who is from Oconomowoc, Wisconsin. “Without them, I wouldn’t be doing as well as I am.”

Transplant innovation begins

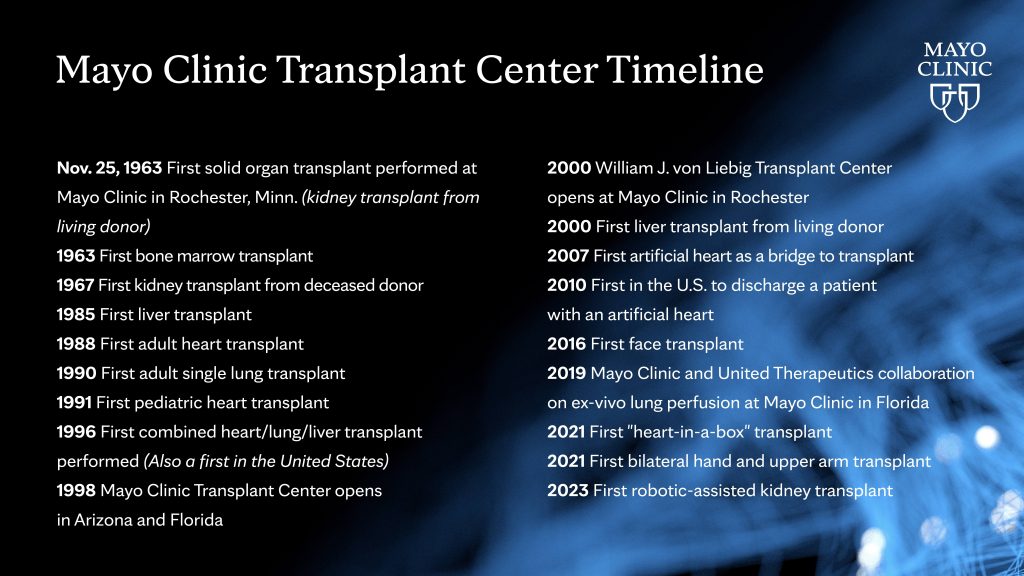

Marking its 60th anniversary this month, the Mayo Clinic Transplant Center is the largest integrated transplant center in the U.S. Mayo’s program includes transplant practices at its campuses in Rochester, Minnesota; Jacksonville, Florida; and Phoenix. Since the program began, Mayo Clinic has performed more than 31,000 solid organ transplants.

“What started at Mayo Clinic in Rochester in 1963 has become a world-renowned transplant program,” says Burcin Taner, M.D., director of Mayo Clinic Transplant Center in Florida.

In October, Mayo Clinic performed its first minimally invasive, robotic-assisted kidney transplant, which also was the first one performed in Minnesota.

These medical bookends, six decades apart, mark significant steps in transplant innovation, says Julie Heimbach, M.D., director of Mayo Clinic Transplant Center in Minnesota.

“It reflects the spirit of innovation and of recognizing serious and complex disease and how Mayo can contribute to moving the field forward,” Dr. Heimbach says.

In 1963, options to care for people with kidney failure were few. Access to hemodialysis, which can replace kidney function temporarily, was limited. Kidney transplantation was a clinical research option in its infancy in the U.S., following the first successful kidney transplant between identical twins performed in Boston in 1954 by a team that ultimately was awarded a Nobel Prize.

Anti-rejection medication to keep the transplant recipient’s immune system from attacking the donated organ was in its early stages but necessary for all transplant recipients except identical twins.

“There were just remarkable hurdles that needed to be overcome,” Dr. Heimbach says. “Even very young people were dying of kidney failure. It was one surgical and medical innovation on top of another that allowed this progress to be made.”

‘My only option was a transplant’

Tired. That’s how Charlotte, a Waukesha, Wisconsin, native, remembers feeling in her youth. But she recalls serious health problems striking almost overnight in her early 20s. Nausea led Charlotte, a newlywed at the time, to believe she may be pregnant. Before she could see her physician, she began having convulsions. Her local doctors could not determine her problem, and she was flown to Mayo Clinic.

Her Mayo team ultimately diagnosed irreversible chronic kidney failure.

Kidney function is necessary to live. These two bean-shaped organs remove waste from the blood by producing urine. They also play a role in controlling blood pressure, fluid balance, red blood cell counts, metabolic balance and bone health. Each healthy kidney is about the size of a person’s fist. They sit in the abdomen along each side of the spine.

Living well with one healthy kidney is possible; that fact makes living kidney donation an option.

Dialysis to clear waste from the blood is a treatment for kidney failure, preceding transplant, but Charlotte had difficulty tolerating those treatments. “My only option was a transplant,” she says.

While a kidney transplant was rare in 1966, so was a patient airplane transfer between medical centers. “Nothing was common back then,” Charlotte says with a chuckle.

Donor testing of healthy and willing candidates to identify a matching blood and tissue type for the needy transplant recipient was also in its early stages in the 1960s. One of Charlotte’s five older brothers, Roland, was identified as her living donor candidate, and Charlotte recalls learning, “We were about as close to being twins as we could be.”

‘She is an inspiration’

Thomas Schwab, M.D., a retired Mayo Clinic transplant nephrologist, was in eighth grade when Charlotte underwent her kidney transplant. By the time he joined the Mayo staff in 1986 and assumed some of her transplant care, Charlotte already had had her kidney for over 20 years.

“Charlotte’s story and outcome is a true inspiration to our transplant teams and especially to those patients in need of a kidney transplant,” he says.

Caring for Charlotte has been a privilege, says Dr. Schwab. “It’s a reason to get up every morning if you can help patients have an outcome like Charlotte has had.”

Watch: Dr. Thomas Schwab talks about transplant recipient

Journalists: Broadcast-quality sound bites with Dr. Schwab are available in the downloads at the end of the post. Please courtesy: “Mayo Clinic News Network.” Name super/CG: Thomas Schwab, M.D./Nephrology/Mayo Clinic.

Charlotte has adhered faithfully to her anti-rejection drug regimen. “I do follow doctor’s orders,” she says. Any side effects from her medical program have been few, and her transplanted kidney function is remarkably normal for a donated kidney that is more than 90 years old, Dr. Schwab notes.

“A kidney transplant is not a sprint. It’s a marathon. It requires paying attention to your health and following the program we recommend. But you’re not out there alone. We have an entire team of doctors, nurse coordinators and surgeons that help along the way,” Dr. Schwab says.

“Over the years, our record of steadily improving patient outcomes shows that research by Mayo Clinic and colleagues worldwide have developed a recipe for long-term success of our transplant patients.”

Pioneering medicine, then and now

Dr. Schwab calls Charlotte a “transplant pioneer” who accepted an opportunity with many unknowns at the time — so was her surgeon, George Hallenbeck, M.D. He led the pioneering team who performed Mayo’s first kidney transplant in 1963. Dr. Hallenbeck’s innovative efforts were not limited to transplant medicine. He was part of the Mayo aeronautical research team that designed the antigravity suit, called the G-suit, a garment developed during World War II that pilots and astronauts wear to keep from blacking out during high acceleration force.

In the early days of kidney transplantation, living donor surgeries were sometimes more extensive than for recipients. Donor surgery required a lengthy incision around a third of the body, and sometimes a rib needed to be removed, Dr. Schwab explains.

Since 1999, living kidney donation surgery at Mayo has been performed with laparoscopic techniques, using smaller incisions to insert surgical instruments and a special camera to remove the donor’s kidney. This minimally invasive approach shortens recovery and increases the rate of living kidney donation, which may be arranged in weeks to months compared with an average four- to six-year wait for a deceased donor kidney.

Even into the 1970s, many patients’ kidney transplants did not survive one year. Today, one-year survival rates for kidney transplants are over 98%, making it the treatment of choice for patients with kidney failure who are eligible for surgery.

October’s robotic-assisted kidney transplant was yet another Mayo milestone. While most kidney transplants are done via open surgery with a 4- to 8-inch incision on the lower abdomen, a robotic-assisted transplant allows the surgeon to make a significantly smaller incision using robotic instruments to complete the transplant, allowing shorter recovery time for the recipient.

Mayo also is focused on research and innovations to expand the kidney donation eligibility pool by helping organs from deceased donors remain viable longer while awaiting transplant. Medical research is being conducted to identify organ failure earlier to delay or prevent the need for a transplant. Mayo transplant experts are developing new practices to help organs last longer after transplantation. In the future, bioengineering of new organs may be possible.

“Our mission is that no patients should die awaiting transplant,” says Bashar Aqel, M.D., director of Mayo Clinic’s Transplant Center in Arizona.

‘I owe all that to Mayo Clinic’

Family and faith have comforted Charlotte during her kidney transplant journey. She recalls praying in the hospital chapel with her mother. “I’m just a strong believer that everything we were doing was the right thing and that everything would turn out,” says Charlotte. “I owe all that to Mayo Clinic.”

For Charlotte, it’s hard to believe how far transplant medicine has come, including a surgeon controlling a robotic instrument to perform the procedure. “It’s really something,” she says. It pleases her to know that today’s female transplant patients may consider pregnancy, which Charlotte and her husband, David, were advised against in the 1960s and 1970s.

Charlotte expresses deep gratitude for her good health during a more than 50-year marriage and a 40-year career as a hospital dietary aide. A widow, she enjoys time with her extended family and quilting and crafting with her sole surviving sibling, her sister, Sharon.

Emotion tugs at her voice when Charlotte speaks of Roland, who, years after donating a kidney, died awaiting a heart transplant. “My brother would be very proud of me,” she says.

To future organ donors and recipients, Charlotte has a message: “I wish them all the best and good meaningful years like I have had.”

Related content:

Related articles

[ad_2]

Source link