[ad_1]

Below is an approximation of this video’s audio content. To see any graphs, charts, graphics, images, and quotes to which Dr. Greger may be referring, watch the above video.

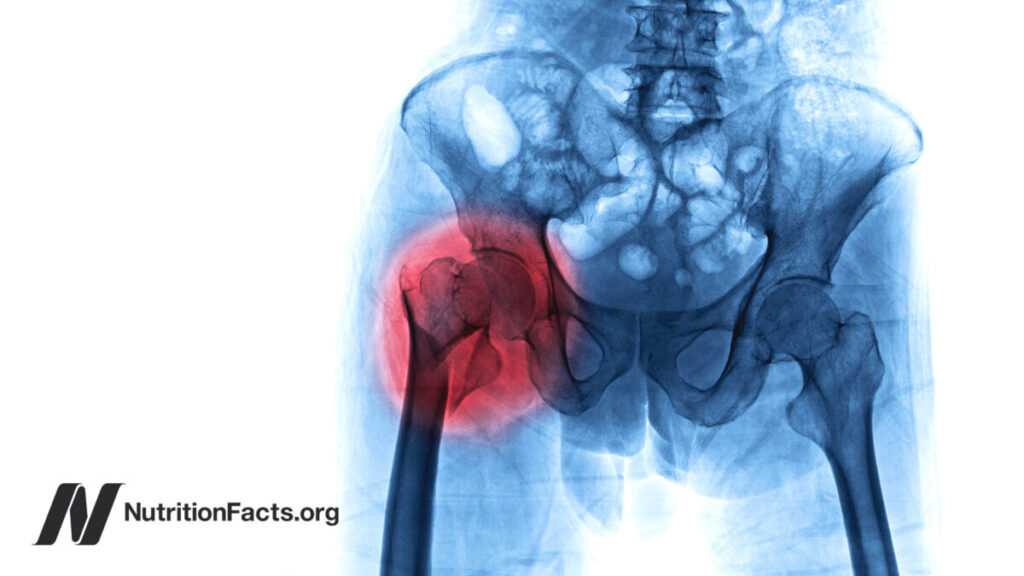

Nearly one in five adults in the world may have osteoporosis. That’s hundreds of millions of people. The word “osteoporosis” literally means porous bone. Now, most of our bone is actually porous to begin with. This is what normal bone looks like inside, but this is osteoporosis.

Bone mineral density is considered to be the standard measure for the diagnosis of osteoporosis. Although the bone mineral density cut-off for an osteoporosis diagnosis is kind of arbitrary, using the standard definition, osteoporosis may affect about one in 10 women by age 60, two in 10 by age 70, four in 10 by age 80, and six or seven out of 10 by age 90. Osteoporosis is typically thought of as a disease in women, but one-third of hip fractures occur in men. The lifetime risk for osteoporotic fractures (for 50-year-old white women and men) are 40 percent and 13 percent, respectively.

The good news is that osteoporosis need not occur. Based on a study of the largest twin registry in the world, less than 30 percent of osteoporotic fracture risk is heritable, leading the researchers to conclude, “Prevention of fractures [even] in the oldest elderly should focus on lifestyle interventions.” This is consistent with the enormous variation in hip fracture rates around the world, with the incidence of hip fracture varying 10-fold, or even 100-fold between countries, suggesting that excessive bone loss is not just an inevitable consequence of aging.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, an independent scientific panel that sets evidence-based, clinical prevention guidelines, recommends osteoporosis screening (such as a DXA bone mineral density scan) for all women aged 65 years and older, and potentially starting even earlier than 65 for women at increased risk (such as having a parental history of hip fracture, being a smoker or an excessive alcohol consumer, or having low body weight). What should you do if you’re diagnosed, or more importantly, what should you do to never be diagnosed? Before exploring the drugs on offering to treat osteoporosis, there are some drugs that may cause it, so let’s start there.

Stomach acid-blocking “proton pump inhibitor” drugs, so-called PPIs—with brand names like Prilosec, Prevacid, Nexium, Protonix, and AcipHex—are among the most popular drugs in the world, raking in billions of dollars a year. But then in 2006, two observational studies out of Europe suggested an association between intake of this class of drugs and increased risk of hip fracture. And by 2010, the growing evidence forced the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to issue a safety alert implicating PPI use with fractures of the hip, wrist, and spine. By now, there’ve been dozens of such studies involving more than two million people who, overall, show higher hip fracture rates among both long- and short-term users at all dose levels.

The irony is that most people taking these drugs shouldn’t even be on them in the first place. These PPIs are only FDA-approved for 10 days of use for the treatment of H. pylori, up to two weeks for heartburn, up to eight weeks for acid reflux disease, and for two to six months for ulcers. Yet, in a community survey, most users remained on these drugs for more than a year, and more than 60 percent of patients were taking them for inappropriate reasons, often wrongly prescribed for “indigestion,” for instance.

Calls to stop this massive overuse from regulatory authorities have fallen on deaf doctor ears. And now that they’re available over the counter, the problem of overuse may have gotten even worse. They can be hard to stop taking, since many patients experience withdrawal symptoms that can last for weeks. In fact, if you take normal healthy volunteers without any symptoms, and put them on these drugs for two months, and then covertly switch them to a placebo without their knowledge, all of a sudden they can develop acid-related symptoms, such as heartburn or acid regurgitation. So, ending up worse off than they were before they even started taking the drugs.

In addition to bone fractures, this class of drugs has also been linked to increased risk of other possible long-term adverse effects, such as pneumonia, intestinal infections, kidney failure, stomach cancer, and cardiovascular disease. In fact, the blood vessel effects could explain the case report “Abrupt-Onset, Profound Erectile Dysfunction in a Healthy Young Man After Initiating Over-the-Counter Omeprazole” (which is Prilosec). Oh, and also premature death.

There are individuals with conditions like Zollinger-Ellison syndrome—stricken with tumors that can cause excess stomach acid secretion—for whom the risk versus benefit of long-term use may be acceptable. But that’s a far cry from the 100 million PPIs prescribed annually in the United States alone.

To deal with acid reflux without drugs, recommendations include weight loss, smoking cessation, avoiding fatty meals (especially within two to three hours of bedtime), increased fiber consumption, and, overall, a more plant-based diet––because nonvegetarianism is associated with twice the odds of acid reflux-induced inflammation.

Other classes of drugs that have been associated with hip fracture risk include antidepressants, anti-Parkinson’s drugs, antipsychotics, anti-anxiety drugs, oral corticosteroids, and the other major class of heartburn drugs, the H2 blockers, such as Pepcid, Zantac, Tagamet, and Axid.

Please consider volunteering to help out on the site.

[ad_2]

Source link