[ad_1]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Friday revised its guidelines for tracking the genetic signatures of viruses collected from people newly diagnosed with H.I.V., a controversial practice used by state and local health departments to curb infections.

The updated policy encouraged health officials to be more transparent with their communities about the tracking, one of many changes sought by H.I.V. advocacy organizations concerned about how so-called molecular surveillance could violate patients’ privacy and civil rights.

But the agency stopped short of adopting more significant changes that some advocates had pushed for, such as allowing health agencies to opt out in states where people can be prosecuted for transmitting H.I.V.

“We’re in a period in which health data is increasingly used in criminal prosecutions, as seen in prosecutions of people seeking abortion care or who have perhaps miscarried,” said Carmel Shachar, a professor at Harvard Law School who specializes in health care. The revised policy did not go far enough, she said, to protect people with H.I.V.

Dr. Alexandra Oster, who leads the C.D.C.’s molecular surveillance team, said the benefits of the program far exceed the risks. “We need to do it well,” she said. “But we need to keep doing it.”

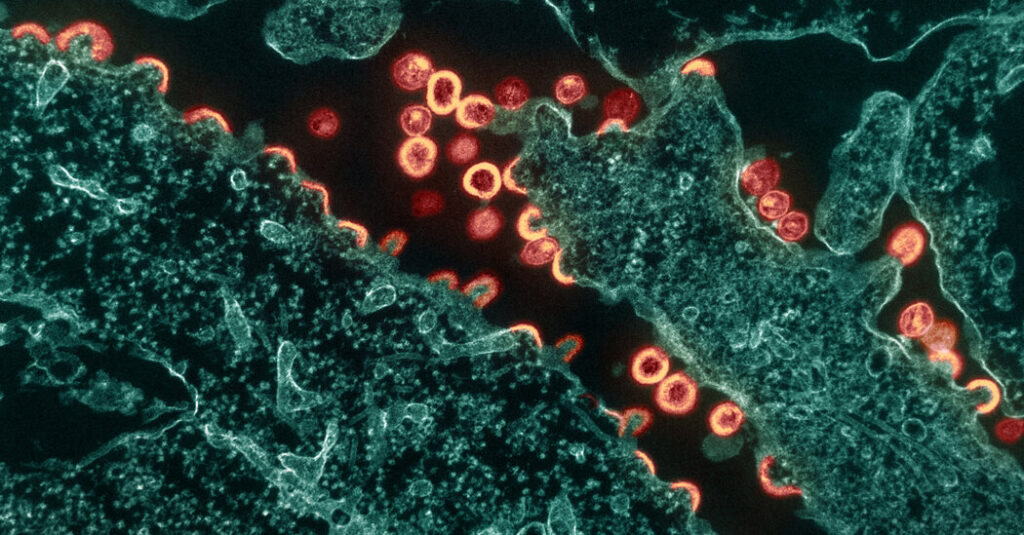

H.I.V. has a distinctive genetic signature in each person that helps doctors decide which drugs are likely to thwart it. But the information can also be used to track its spread through a population — including identifying clusters of people who carry closely related viruses.

The C.D.C. has for decades used molecular surveillance to track flu, salmonella and, more recently, Covid.

In 2018, the C.D.C. began requiring health departments that received federal funding for H.I.V. programs to share such data gleaned from people with the virus. Patients do not have to be informed that their viral samples are tracked.

Molecular surveillance has identified more than 500 H.I.V. clusters in the country since 2016, the C.D.C. said. Health officials can then interview people in the clusters to identify their sexual or drug-use partners and connect them to testing, needle exchanges and medications that block transmission.

[ad_2]

Source link